Some links are affiliate links. Please see more here.

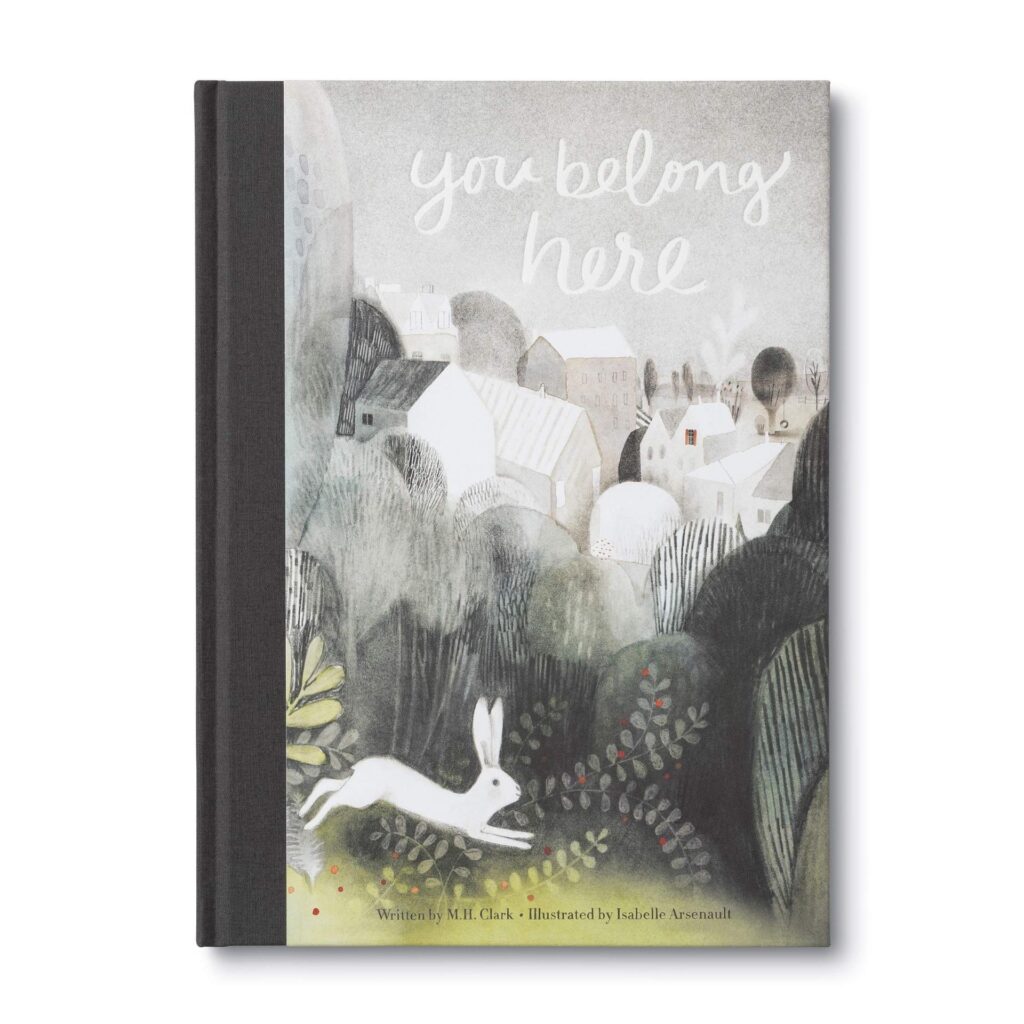

SUMMARY: One of the tests of a book for me is: Do I see myself giving this book to someone I love and admire? And if so, will their child also love it and benefit from it? You Belong Here, a picture book in verse written by M. H. Clark and illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault easily passes that test and so it’s one of my go-to books to give to expecting parents and grandparents or any person who is just so excited to give a child that sense of belonging. This is the bedtime book that I read to both of my children when they were infants, so it holds a special place in our family. You Belong Here is both a beautiful celebration of belonging to a particular person or family or home and also about having a place in humanity and belonging to the world. There is a deliberate vagueness in both the image and the text that allows for imagination, which also makes You Belong Here more universal and inclusive of all families, whatever form they might take. Additionally, this book is a good choice to read to your infants because it taps into what appeals to their developing minds and hearts. Every time I read this book (which has been a lot in the past four years!), I marvel at its ingenuity and its general loveliness. I hope you and your children love it, too!

Listen to the Podcast Episode:

Books Mentioned in this Episode:

You Belong Here by M.H. Clark, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault

The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living by Meik Wiking

Podcast Transcript:

Hello Everybody! Today I’m going to be talking about the second book in our Bedtime Book Series. Last week we talked about what is probably the most famous children’s bedtime book, Goodnight Moon, by Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd, so if you missed it and you’d like to begin with a classic bedtime book, you can go back and listen to Episode 15. This week’s book is not a classic, but rather a very recent book that was published in July of 2016, although I really hope it does become a classic because it’s so excellent. It’s entitled You Belong Here, and it’s written by M. H. Clark and illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault. This book was given to me when I was pregnant with my first son, James, and it quickly became my go-to book to read aloud to him in the month before he was born and then I continued to read it to him through the newborn and infant stages up until he started requesting his own books at bedtime. And, incidentally, if you’d like to hear about why I read aloud to my own stomach like a weirdo when I was pregnant, you can go back and listen to Episode 4 where I talk about the benefits of reading aloud to newborns and even to pre-borns. Anyway, when James was a newborn and the days and nights all sort of jumbled together in a sleepless haze, my husband Eric and I decided to start trying to institute some sort of bedtime routine to help us 1) keep track of the time because neither of us could remember what day of the week it was or when we had last sponge-bathed the baby or, let’s be honest, when we had last showered ourselves and 2) to help us start trying to gently nudge James onto some sort of semblance of a schedule. We decided as part of our nightly routine to read this particular book to James because it was the one book that we both agreed wasn’t too sappy or problematic, but still reminded us how happy we were to be parents—even if we were covered in someone else’s fluids and we were starting to fully appreciate why people use sleep deprivation as a form of torture. And, we also hoped that it would make James feel calm, safe, and loved before he had to separate from us and go to sleep. And, miraculously, I definitely think it worked, so we also read it to Luke before he went to bed as a baby and it seemed to have the same effect on him. Now that James is older, he mostly chooses his own books at bedtime, and so does Luke, but sometimes they will still choose this book, especially on those days when they want to cozy up with us or if they’re feeling sick or sad or something. It’s become a sort of comfort object, which, as a book-lover, makes sense to me. I have a handful of favorites from my childhood that I love to revisit when I’m sick or I’m sad or I just want to read something particularly… hyggelig, as the Danish might say. Side note as an explanation for the Danish word: I just started listening to this hilarious podcast called “By the Book” where these two women pick a self-help book and live by it for 2 weeks, so I revisited The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living and now all I want to do is knit some wool socks and burn 13 pounds of candles and eat my weight in dark chocolate and make every corner of my house into a nest. But I digress.

Okay, so let’s talk about why You Belong Here makes for a wonderful bedtime read for you and your child:

First of all, just a disclaimer of sorts: You Belong Here is a rhyming picture book and it is actually more of a poem than a story in that it doesn’t really have a plot or a narrative, but rather it conveys its message through verse. So, yes, it is a poem—which, I know, turns some people off because poetry just isn’t their thing. And I understand that. But even if you aren’t a poetry person, please bear with me because I think you’ll still like this book. It does what I think the best poems do which is to focus on small, intimate, or personal things, but simultaneously make them at once profound and universal. So this book, YOU Belong HERE is both a beautiful celebration of belonging to a particular person or family or home and also about having a place in humanity and belonging to the world. But it does so in a way that isn’t, you know, so sweet that it’s sickening. There are plenty of rhyming poetic picture books that make me cringe or roll my eyes because they are so cloyingly saccharine and they are trying so hard to pull at my heartstrings that instead they make me nauseous, but this book is not one of them. I think You Belong Here avoids becoming too sentimental or mawkish because of the way the poem is structured, with two different threads that balance each other out and then sort of become interwoven…but we’ll get to that in a minute.

For now, if I haven’t convinced you to read this because of my promise that it isn’t a bad poetic children’s book, let me try another approach and tell you that this book is a good choice to read to your infants because it taps into what appeals to their brains at this time. By virtue of the fact that this book is a poem, it has a more musical sound pattern and, as we know from Episode 4: Why You Should Read Aloud to Your Newborn, a baby’s sense of hearing is highly developed in many ways and babies find music and rhymes very appealing. So this book gives infants the more complex listening experience that they crave. Plus, the poetry has a gentle rhythm and a patient, steady pace, which is soothing for children and might actually make your baby sleepy—which is always a win for a bedtime book. Additionally, visually, even though this book isn’t what I would call a high-contrast book, it does have a lot of black and white and gray and then little splashes of red, which are the first colors a baby can see. And, the scenes with the animal close-ups in particular will also be attractive to very young infants because of the way they stand out against the backdrop of their environments. For example, both of my infant sons were really attracted to the illustration of the hares in the nighttime desert.

Okay, so let’s talk about the book’s structure and those two threads of thought (for lack of a better word) that I mentioned. The poem is made up of quatrains (or four lines that make up one stanza) where each alternating line rhymes with the other, or, in other words, an ABAB rhyme scheme. But, what is unique is that the poem also alternates in subject matter or idea or motif. Basically, you could look at this book as having two separate ideas that are woven together to give us one message. The first idea thread is more intimate: the narrator is talking to one specific child and how that child belongs with the narrator. But then the poem shifts to incorporate the second thread, which opens up this idea of “belonging,” expanding it to make it more general and universal by talking about various creatures and other forms of natural life and where they belong. For example, one of the quatrains that is part of the first, more intimate idea thread is:

And you belong right here, where you’re home

and where I hold you close

of all the wonders I’ve ever known

you’re the one I love the most.

While one of the quatrains in the second, more universal thread that, again, expands this idea of belonging, is:

And the otters belong by the banks of the stream

and the cattails belong there too,

and the carp belong where the water runs green

and the shadows all run blue.

What is nice about the alternating motifs is that you don’t get bombarded by the sentimental stuff; the idea that the child listener’s place of belonging is with the narrator is carefully, beautifully woven through the poem, but in a very gentle, natural way. It isn’t intense or melodramatic or showy, which can be off-putting not only for adults, but also for children who even at a young age are able to detect when someone is laying it on thick. But, reassuring your child in a non-showy or affected way that they are loved and that they belong somewhere and that they belong to someone and that they have a place in the world just like everyone and everything else, is such an important concept for your child to internalize, even at such a young age. Our sense of belonging as human beings begins with our attachment to a caregiver and our fundamental need for that attachment. As it is, our sense of belonging as children (and as adults, too, for that matter) is profoundly impactful to our physical and mental health. When children feel that they have support and are not alone, they cope more effectively with stress and with difficult situations that may arise in their lives. And, if they are able to cope well with these difficult situations because they feel supported and have a sense of belonging, the physical and mental impact of these situations on them decreases. Conversely, studies have shown that children who lack a sense of belonging or who have not achieved a healthy attachment in their young lives have lower self-esteem, can feel rejected, depressed, mistrustful, and have a negative worldview. So, it’s incredibly important that we foster a sense of belonging in our kids, right from the very beginning.

Also, just a little side-note about the design of the book: I really like that they chose to have the actual text of the book take two different forms, so that the parts that discuss the various creatures and natural life (the trees belonging in the wild wood; the otters belonging by the stream) are in a typeface, while the parts that speak to the child directly (like for example, “YOU are a dream that the world once dreamt; And YOU belong right here, where YOU’RE home”) look handwritten, almost like they are a letter to the child listener/reader. It’s another subtle way to add another layer of intimacy to those parts of the poem without being too over the top about it.

AND, as another sort of side note here, one of the nicest things about You Belong Here and what makes it a great book for all sorts of families, is that it could be about a loving relationship between any two people who care for each other. The narrator is never described as a parent. For our purposes today (since this is a picture book and this is a podcast about children’s literature and it’s the book that I personally read to my very young children at night), when I talk about it going forward I’m going to speak as if the narrator is the parent/caregiver and the person s/he is addressing when s/he says “And I belong here with you” is a very young child. But, what’s really lovely is that, yes, the relationship could be between a parent and a very young child, but it could also very well be the relationship between a parent and an older child who is going off to college, OR a parent and a newly adopted child, young or old, OR grandparent and a child, OR an aunt or uncle and a child, OR a foster parent and a child, OR a godparent and a godchild—basically, any loving relationship between a caregiver and a child. You get the idea.

Okay. Moving on. Another reason this book is great for people besides infants and their sleep-deprived but completely besotted parents is that the second thread of the poem, the part that focuses on animals and other natural life, is really interesting to older toddlers and preschoolers who are learning more about living creatures and their environments. I like that M. H. Clark chose some less celebrated animals in addition to the bunnies and bears and foxes that so often appear in picture books for children. Bunnies (well, hares) and bears and foxes do appear, but they appear alongside carp, lizards, and otters. And, what’s more, their habitats are described carefully and vividly but also with economy; the descriptions aren’t flowery, but rather very precise. Clark chooses the perfect words to describe the creatures and where they belong, which complements the puzzle motif in the illustrations that we’ll get to in a minute. But to finish this original thought, I also like that the plants and other natural elements are also more diverse than in other picture books, with Clark highlighting things like sage, cattails, pines, clover, dunes, and even comets. These are really great talking points when you read this book aloud with a toddler or even a preschooler because they can help to broaden children’s vocabulary and can act as an entry point into other enriching discussions, like how a comet is formed or where sand dunes occur.

Okay, let’s move on to the illustrations:

As in all the most wonderful picture books, the text and the illustrations of You Belong Here really complement each other and help to convey the book’s ultimate themes and messages. Isabelle Arsenault, the illustrator, has a very distinct style that isreally perfect for this book and for the way that M. H. Clark writes. Arsenault’s style is modern (and by that I mean you can tell it’s contemporary and wasn’t drawn 100 years ago), but it still has a sort of old-fashioned twist to it. It also has a French feel to it, which is perhaps because Arsenault is French Canadian, but also maybe because the text that looks handwritten reminds me of the French style of cursive writing.

For the images themselves, Arsenault uses pencil and colored ink to create a very fluid, dreamy effect. The illustrations are done with mostly muted, natural colors like charcoal and dove grays, browns, seafoam greens, and eggshell whites, but with occasional splashes or dots of red ochre or burnt orange. In the pages that feature animals, the creatures themselves are pretty much devoid of color, which, as we will see in a minute, is purposeful. They look like delicate pencil outlines on white paper, with only the key identifying features of each animal drawn in pencil with a little bit of smudging or shading to make them just slightly more naturalistic.

The pages in which the narrator addresses the child listener, however, do not include any images of people or even other creatures, but instead the focus is on place, either houses grouped in a cityscape or in a small town or a house in the wilderness. In each of these illustrations, there is one house that has a window that is illuminated and the soft yellow light stains outward into the rest of the picture. I really like that Arsenault chose to focus on the environment in these sections because, by not including any images of people, there isn’t any reference point or suggestion for who the narrator and the listener are or what they look like or what their relationship looks like. It could be a mother and a child, a father and a child, a grandparent and child, a foster parent and a child, a godparent and a child—basically any caregiver and a child. The narrator and the listener have no gender, no race, no age, and no sexual orientation, so therefore they could have any gender, race, age, or sexual orientation. They could be differently abled, they could be a part of a family with two parents, or a family with one parent, or a family with two dads or two moms or any other combination of people who belong together. There is a deliberate vagueness in both the image and the text that allows for imagination so, in this way, by complementing the language of the book, the illustrations make You Belong Here more universal and inclusive, which I just love.

And now, to go back to the pages that feature animals: as I mentioned, the animals themselves are left almost completely blank and devoid of color, but you don’t really realize or notice this or understand that this is purposeful until you get to the penultimate two-page spread. The quatrain that accompanies this spread goes like this:

Some creatures were made for the land or the air

and others were made for the sea.

Each creature is perfectly home right there

in the place it belongs to be.

This quatrain acts as almost a summary of the other verses that detail how each animal belongs to a particular place, saying that some creatures might belong in the water, some in the air, some on land, but no matter where they live, that is their home, they fit in perfectly, and they are meant to be there. And what’s so clever is that the image to go along with these four verses is a two-page spread of a wooden knob puzzle, the beginner kind of puzzle that very young children are first able to do. And, if you look closely, you notice that the animals Arsenault has created here in full color are actually the same blank animals from the previous pages, drawn exactly the same way except now completely filled in with color and ready, so to speak, to be put into their places. Each animal on these two pages has a bright, flame-red knob and there is also a set of hands holding the image of the baby turtle by this little red peg and fitting it into its place. And again, what I like here is that the hands are completely devoid of color or even shading in order to keep their anonymity and universality. AND, what’s more, the puzzle board or the base of the puzzle is actually the illustration that Arsenault created of the adult and baby turtle that was on a previous page of the book. So, it’s as if the whole book is a puzzle that is waiting for the readers to fit each piece perfectly into place. It’s such a powerful rendering because the reader or listener of the story can then imagine putting all of the pieces into place, which means that Arsenault is allowing the child reader to participate in creating a place where everything belongs. Therefore, in this way, the child is playing an active role in the achievement of the ultimate message of this book, which is that everything and everyone has a place in the world, everyone and everything belongs. It’s really brilliant and moving.

Finally, to wrap up our discussion on the illustrations and how they convey the message of M. H. Clark’s words, when you come to the end of the book you will notice that the first illustration and the last illustration are of the same cityscape. The first quatrain that accompanies the first illustration goes like this:

The stars belong in the deep night sky

and the moon belongs there too,

and the winds belong in each place they blow by

and I belong here with you.

And in the first illustration, one house in the cityscape is left blank; it’s merely the outline of a house, and inside the blank space is the last line of the first quatrain, the words: “and I belong here with you.” So, after finishing the book and becoming aware of the puzzle motif, we realize that this blank house is like the animals that are just sketches devoid of color, just waiting to be filled in. So then in the last illustration of the book that goes along with the last quatrain that ends “and you’ll always belong with me,” this previously blank outline of a house from the first illustration is now filled in the red ochre color that appears throughout the book, with a single red flower of the same color in the window. The rest of the cityscape is colored in with those muted natural tones, so the house really stands out and draws your eye. And because this house is the same red as the knobs of the puzzle pieces, it subtly emphasizes that this home, the place where the narrator and the child are together, is the right fit, this is where they belong. So the last quatrain goes like this:

And no matter what places you travel to,

what wonders you choose to see,

I will always belong right here with you,

And you’ll always belong with me.

The last quatrain talks about the second person (the child) traveling away and seeing other places and “wonders,” but emphasizes that the narrator and the child will always belong together, as if the narrator is a safe haven for the child where s/he/they will always belong. As I mentioned, the two-page illustration is mostly painted in variations of black, white, gray, and brown, but in the space around the red-orange house, the other buildings and the trees and the sky take on a bit more color, with some pale blues, yellows, and greens. It almost looks as if that red house is a flame that lights up the rest of the page and allows you to see the color of the other things surrounding it. It’s like the color is slowly staining outward. So, the red house, then, brings another idea to life: that in a drab, colorless world the person who is your safe haven shines like a beacon and, what’s more, brings light and color and meaning to the rest of your existence. It’s a really beautiful idea and it is executed so exquisitely here. Every time I read this book (which has been a lot in the past four years), I marvel at its ingenuity and its general loveliness. One of the tests of a book for me is: Do I see myself giving this book to someone that I love and admire? And if so, will their child also love it and benefit from it? This is one of the books that easily passes that test and so it’s one of my go-to books to give to expecting parents and grandparents or to put in a gift basket for a new baby. It’s a great baby-shower gift because, first of all, the expectant parent will probably not receive duplicates of it because, as of yet, it isn’t as well-known as, say, Goodnight Moon or Guess How Much I Love You. But second, it also is such a perfect book for a person who is just so excited to give a child that sense of belonging.

And one last thing before I end this episode. This has been a very turbulent year for all of us, but especially I think for children who have had to adapt and cope with so much in 2020. So, I just wanted to mention that, additionally, this could be a great book to read with your child this year just to remind them how much you love them and how no matter what, they always belong with you. And, this book could be a great tool if you are trying to teach your older children about mindfulness to help them cope with the stress of the global pandemic and all of the uncertainty in the world. You Belong Here can be such a grounding and helpful book because it focuses on one thing: a sense of belonging. This book calls attention to the present moment between the narrator and the child, sitting together reading the book, and the relationship that exists between those two people. So while the book does move us from scene to scene, helping us to notice the similar relationships that exist between other creatures and places and things, everything always relates back to this fundamental, comforting sense of belonging. In this way, the book acts as a model for us and for our kids on how to train our minds to be better at focusing and being present in the moment and choosing which thoughts we want to act on and which ones we want to let pass. It might seem like a lot for a little bedtime book, especially for very young children, but because this book allows our thoughts to expand to notice other things, but then always brings us back to this central idea of belonging, it models for us how to redirect our thoughts when they start to veer off course and stay in the moment. Honing this ability to stay present and focused helps our kids build a strong and connected relationship with their minds, which is so crucial, especially right now.

And that’s it for this episode of the Exquisitely Ever After Podcast! I would love to know if you’ve read You Belong Here with your family or if you have another go-to book for bedtime that you read with your children. Let me know by sending me an email at christina@exquisitelyeverafter.com or you can DM me on Instagram at exquisitelyeverafter or you can leave me a comment on the blog post for this episode at exquisitelyeverafter.com/episode16. And if you liked this episode or this podcast in general, please do subscribe, it’s totally free and by subscribing you ensure that you don’t miss any new episodes. Also, if you could leave me a rating or a review on iTunes or share this podcast with a friend, that would be amazing! Word-of-mouth recommendations are the number-one way people find this podcast so the more that you share it, the more our community grows! I really appreciate that you took time to listen to me talk about children’s literature today! Take care everyone, keep safe, and of course, keep reading!

Pin This Episode For Later:

Why did it take me until episode 16 to start listening to this? It’s like getting together with your best mom friend for coffee, if your best non friend was also a brilliant authority on all things children’s literature. Smart, poignant and thought provoking, and just generally soothing at a time when, really, we could all use a little hygge. Can’t wait to back track! 🙂