Some links are affiliate links. Please see more here.

SUMMARY: Embracing diversity and being accepting and inclusive of all kinds of people no matter their race, religion, physical abilities, gender identity, or economic status is crucial to making sure that we raise kind, empathetic people who will flourish in multicultural societies and positively contribute to our global community. If we want to raise people who feel free to express themselves, who feel that they can accomplish anything no matter their race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or economic status, and who appreciate and respect the contributions to the world made by ALL people, it’s really important that we start sending these messages to our kids early on in their lives. Reading picture books that model attitudes of openness and acceptance is one of the easiest ways we can do this without it becoming too complicated or overwhelming for our kids—or for us! The nine engaging, brain-building, and empathy-growing picture books that I talk about today will help you teach your young children what it means to be an inclusive person AND how to practice inclusivity in their everyday lives.

Listen to the Podcast Episode:

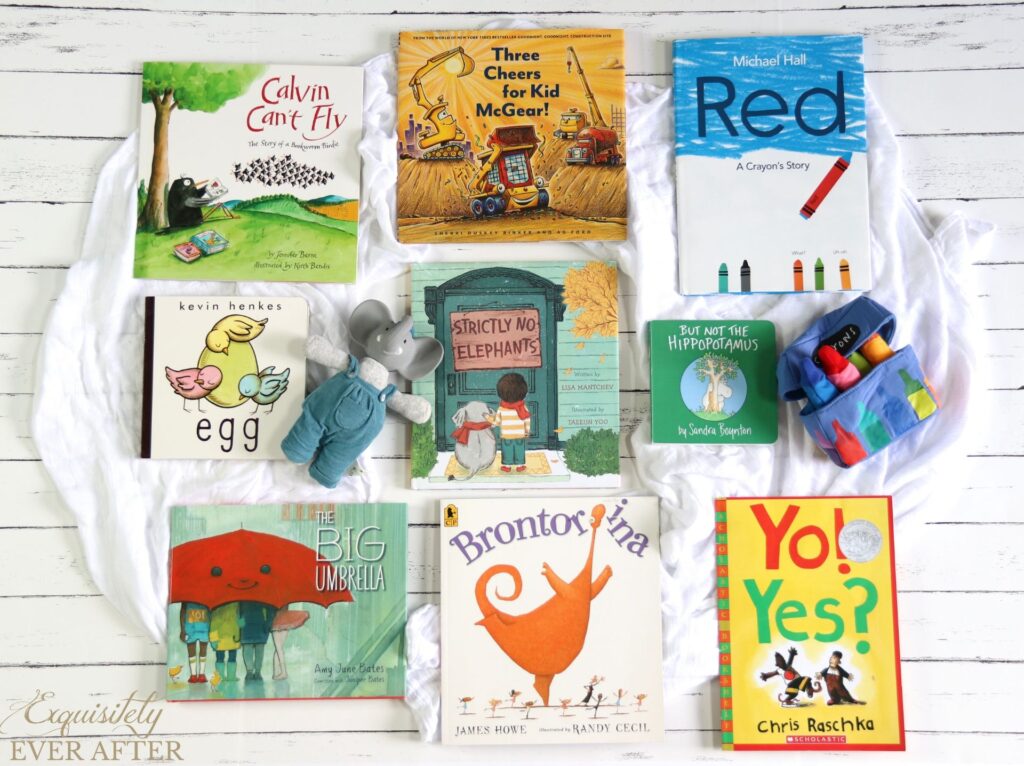

Books Mentioned in this Episode:

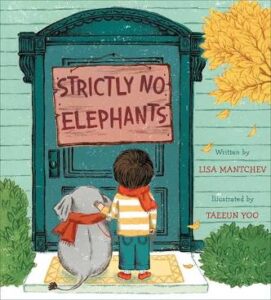

*Strictly No Elephants by Lisa Mantchev, illustrated by Taeeun Yoo

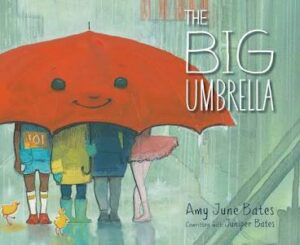

*The Big Umbrella by Amy June Bates, cowritten with Juniper Bates

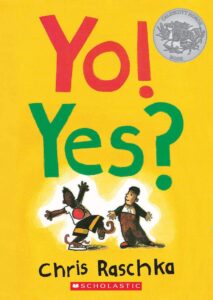

*Yo! Yes? by Chris Raschka

*Three Cheers for Kid McGear! by Sherri Duskey Rinker, illustrated by AG Ford

Goodnight Goodnight Construction Site by Sherri Duskey Rinker, illustrated by AG Ford

Mighty Mighty Construction Site by Sherri Duskey Rinker, illustrated by AG Ford (based on the illustrations by Tom Lichtenheld)

Construction Site on Christmas Night by Sherri Duskey Rinker, illustrated by AG Ford

*Calvin Can’t Fly: The Story of a Bookworm Birdie by Jennifer Berne, illustrated by Keith Bendis

*Brontorina by James Howe, illustrated by Randy Cecil

*Red: A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall

*But Not the Hippopotamus by Sandra Boynton

But Not the Armadillo by Sandra Boynton

*Egg by Kevin Henkes

Note: Books marked with * are the focus books of this episode.

Elephant toy (similar)

Gustave Caillebotte’s “The Floor Scrapers”

Podcast Transcript:

Hello Everyone! I’m excited to dive into today’s episode about reading books about being inclusive to young children because I think it’s so imperative that we engage children in this effort, especially right now. As the mother of a preschooler, inclusiveness was one of the most important concepts that I wanted to teach my son before he entered a classroom. Making sure my child felt included and, and even more importantly, was inclusive to other children was a top priority for me and my husband. I mean, even though of course I wanted my child to be included by his peers (nobody wants their child to be the one who is left out) I honestly was even more concerned about making sure that he knew that, as a person, even a little person, you have a great deal of power to influence your community. We talked a lot about how you can either make people feel like they belong and that they are one of your friends, or you can make them feel like they don’t belong and that they aren’t one of your friends, and that this is a choice you make every day. And I also emphasized that inaction is still an action. Or, in preschool terms, if someone is feeling left out, not doing anything, not trying to include them in your game or whatever you’re playing, also makes a person feel like they don’t belong. I wanted to make sure that my child knew that if someone was feeling sad or left out, he had a special power to change that, just by saying hello or asking if they wanted to play. I really want my kids to know that it’s not okay to stay silent, that if they see someone who’s being left out or who just might be too shy to join in on their own, that it is their job to try to help that person feel like they belong to the group.

Embracing diversity and being accepting and inclusive of all kinds of people no matter their race, religion, physical abilities, gender identity, or economic status is crucial to making sure that we raise kind, empathetic people who will flourish in multicultural societies and positively contribute to our global community. I think a lot of the time we talk about inclusion as something that we should strive for because being inclusive is morally the right thing to do. And we also talk about being inclusive as something that primarily benefits others. Which, yes, of course it is morally the right thing to do and of course it does benefit others which is reason enough for us to practice it, HOWEVER, being inclusive is also so beneficial to the people who practice it. Everyone has something unique and interesting to offer the world and when we include everyone we gain relationships and experiences that enrich our lives and broaden our perspectives. By recognizing and embracing difference, our worldview expands AND—perhaps most importantly in the current state of the world—when we are inclusive, we aren’t divided. When we teach our children to be inclusive of others, we’re teaching them that we are all part of one whole and on the same side; we’re all on Team Humanity.

So, this sounds great in theory, but today we’re going to talk about how we can actually teach our children this. It’s sometimes daunting as a parent to know where to begin. We obviously know that if we want our children to embrace diversity and be inclusive of others, we must model attitudes of openness and acceptance and be inclusive ourselves because our children are always observing what we do. But beyond that, how can we take action and push the needle forward on this every day without it becoming too overwhelming for us or for our kids? Now, this is going to come as no surprise to you because, I mean, you are subscribed to this podcast about reading children’s literature to cultivate kind, intelligent, and successful kids… I mean, I hope you’re subscribed. If you aren’t, please do! It’s free and we’d love to have you! … See! Inclusiveness! Anyway, this isn’t going to be a shocker for you, but reading books to your child that show diversity and model inclusiveness is one of the best and easiest ways for you to help your child become a person who includes others. Reading books with your child that celebrate diversity and model attitudes of acceptance and inclusion is such a great way to reinforce the messages and values that you’re trying to communicate to, and instill in, your child. And it’s so easy because we don’t have to try to come up with age-appropriate scenarios or role-play or carve out any extra time to create teachable moments or anything like that ourselves. All we have to do is read a book together at bedtime or quiet time or whatever other time of day you and your family normally read aloud and, while we’re reading, have an organic conversation with our children about the scenarios in that book. So, in this way, we can use children’s literature and the conversations we have with our children about the books we read to address issues of bias and discrimination and their effect on a person’s feelings and self-worth when they are excluded for these reasons. And we can also use these books as a way to help our children problem-solve in their real lives because, by reading stories that model inclusion, our kids can better brainstorm ideas about how to practice inclusiveness in their own lives since they’ve already witnessed other people do it in fiction.

So the 9 books I’m going to walk you through today can help you teach your young child to be aware of differences–and accepting of differences–and will also give you and your child strategies to help your child practice being inclusive. Most of these books are appropriate for preschool, kindergarten, and early elementary school children, although a few of them stretch a bit in either direction. And the last two I’m going to cover are appropriate for toddlers because it’s never too early to start communicating these values and ideas to our kids.

Okay, now on to the books!

First up is Strictly No Elephants by Lisa Mantchev, illustrated by Taeeun Yoo, which is one of my most favorite picture books ever and one that I often give as a gift to expecting parents. Here’s the plot: It’s Pet Club Day and a little boy and his tiny pet elephant get ready to attend, wearing matching red scarves. After walking through the neighborhood and avoiding the cracks in the sidewalk that make the little elephant nervous, they arrive, only to find a little girl blocking the doorway and pointing to a sign on the door that reads, “Strictly No Elephants.” Crushed, the little boy leaves with his little elephant and they walk dejectedly through the rain until they see a little girl sitting on a bench holding a skunk. She asks if they, too, were rejected by the Pet Club and the two children decide to start their own club and invite everyone—no matter what type of animal they have for a pet—to join. They find a treehouse for their club location and make their own sign, which reads “All Are Welcome.” The story ends with the little boy inviting the reader to join them, too, and the illustration shows all of the children happily playing with their unusual pets. Even the little girl who initially rejected them is seen peeking in the doorway with her dog.

I bought this book from the Curious George Bookstore in Harvard Square in the fall of 2016 the first time we went back to Cambridge for a visit after having my oldest son James. He was just a couple of months old at the time, so it was a book whose message I knew he would have to grow into, but because the illustrations really help to support the message and because the story is comprised of short, direct sentences, I knew it wouldn’t be too long and that this book could really appeal to a young toddler even though the target age range is supposedly 4-8 years old. I love—and both of my toddlers have loved—the illustrations, which are winsome and sometimes gently humorous, like when the little boy carries his little elephant over the cracks in the sidewalk. And the parade of all the animals and their kids walking to the treehouse is so great. My kids particularly loved looking at the narwhale in the fishbowl being pulled in the wagon. And, incidentally, this book is also awesome because it can help you to teach your young child about animals that they don’t normally see in picture books or in their daily lives, like the narwhale, but also the armadillo, the bat, the penguin, the hedgehog, etc. And, finally, I love the way the weather reflects the sadness the boy and the elephant feel when they are turned away: the two-page spread is a wash of blue shadows and rain, and only the boy, the elephant, the girl, and her skunk have any other color to them. It’s such a simple, clear way to get across the feelings of the little boy and I also love that because the little girl with the skunk is the only other bright spot in the gloom, this image subtly sends the message that connection with another person is how we can find happiness and acceptance. When you are reading this book to your child and he sees this illustration, you can ask, “How do you think the little boy and his elephant are feeling right now?” and then you can draw his attention to the girl by saying something like, “But look, there’s someone else looking sad, too… I wonder what she’s sad about? Maybe the little boy will notice her, too…” In this way, not only are you helping your young child hone his reading and visual comprehension skills, but you are also highlighting the messages of the book without being too obvious about it.

As I mentioned before, the actual text of this book is very short and direct; it communicates a lot in very few words. So even though it has some really profound messages, it gets them across simply and gently and with a lot of charm. For example, I love the line: “His is a very thoughtful sort of walk” and we see the elephant holding the umbrella for the little boy in the illustration. Here the author and illustrator give us one word, “thoughtful,” to describe the walk and one simple image and, right away, your child understands that the elephant and the boy take care of each other. And I love the unassuming refrain: “That’s what friends do: lift each other over the cracks”; or “That’s what friends do: brave the scary things for you”; or “That’s what friends do: never leave anyone behind.” It’s straightforward enough to be understood, but it’s not preachy, so it doesn’t make the book too saccharine or self-righteous. And it’s stated as a fact, not a directive; it’s not “That’s what friends should do.” It’s just: “That’s what friends do.” To us adults reading the book to our kids, this is poignant and touching in its simplicity, but for small children this is also really valuable information. As I mentioned in Episode 2, very small children and preschoolers associate friendship with play and having fun, happy experiences with other people; they don’t yet understand what it truly means to be a good friend or the attention, care, and mutual respect that it requires. So, for very young children who are just figuring out the way friendship works, this kind of straightforward relaying of facts is helpful. They can, like, download this message into their brains: being a friend means never leaving anyone behind. Got it. Check!

I think another great thing about this book is the agency the children have and the whole brainstorming element that it models. I like that the little girl and the little boy don’t have to go to anyone else to figure out what to do. The little girl asks the little boy if he was also rejected and they both come up with a plan to include everyone in Pet Club Day. It is so empowering for little kids to know that they have the ability to be agents of change and that they can make things better not only for themselves, but also for other people.

And just one last thing: I like that when the little girl tells the little boy that the sign didn’t mention skunks, but the other kids don’t want her and the skunk to play with them either, his response is “They don’t know any better,” but it doesn’t just stop there. This book shows us and our children that there is an antidote to ignorance and that is teaching, not retaliation. The little boy doesn’t accept that the other kids can exclude people because they don’t know any better and just let them have a monopoly on pet clubs, but he also doesn’t retaliate by turning around and making a rival club that only includes unusual animals. This little boy, as young as he is, understands that everyone is responsible for becoming better than the environment in which they grow up. He knows the answer is to rise above the pettiness, no pun intended. So, when he and the little girl make a club of their own, the sign that they put on the door crosses out the parts that exclude anyone. So Strictly No Strangers No Spoilsports is crossed out and instead, the sign reads in capital red letters: “ALL ARE WELCOME” and they even include the little girl who was responsible for excluding them from the original Pet Club. It’s such a great message and when you read this book with your child, you can draw her attention to the crossed-out words and have a brief conversation about why they’ve been replaced with “ALL ARE WELCOME.” And you can call attention to the little girl and her dog who are peeking in and talk about why she might want to join this new club, or have your child verbally list the reasons why this new club might be better than the original club, or you might simply just state, “Oh, look! They’re even letting that little girl and her puppy play with them. That’s so kind of them.” So by reading this book, in just a few short minutes, you can reinforce how diversity should be celebrated, why inclusiveness is important and benefits everyone, and what it means to be a good friend and an inclusive person.

Okay, the second book I’d like to recommend is The Big Umbrella, by Amy June Bates, cowritten with her daughter Juniper Bates. If you like the charming illustration style of Strictly No Elephants and if you like the color palette of Strictly No Elephants, this is another book you’ll love. Its language is also very sparse and it’s even simpler and more straightforward than Strictly No Elephants because it doesn’t really have a plot, but rather it is just delivering a message through words and pictures. So, for this reason, even though the age range is supposedly 4-8 years old which is the same as for Strictly No Elephants, this is one of those unique books that actually works best for the extremes of the age range rather than those who fall in the middle. I think very young children will really love and engage with the illustrations while older children will respond well to the message and understand the book on a deeper level. That isn’t to say that this book is a miss for the kids in between, like the kindergarteners and first graders, but I find that these youngest elementary school kids respond better to picture books with more of a plot and more character development.

The book begins, “By the front door there is an umbrella.” And then it shows a child picking up the umbrella to shelter her from the rain and the book continues to describe the umbrella with only a very few words, saying that it is a big, friendly, umbrella that likes to help, give shelter, and gather people in. As the book progresses and the little girl walks through the rain, she encounters more and more people and creatures standing in the rain outside the umbrella. She pauses in front of each person and each time the umbrella expands to fit everyone underneath, no matter who they are or what they look like. And even though it seems like there won’t be enough room, each time another person appears, there is. The book ends with the words, “There is always room.”

As I just mentioned, this picture book has a very friendly, winsome illustration style. I love the cheerful, smiling, red umbrella. Its expression is just so sweet and welcoming and it’s such a unique idea for a main character. I find the illustration of the umbrella and the sun smiling at each other at the end to be particularly touching for some reason. And I also love the huge variety of people and animals and creatures that Amy June Bates squeezes under it. There are not only representatives from many diverse races and ethnicities, but there are also old people, young people, differently abled people, tall people, short people—all kinds of people. I especially like that Amy and Juniper Bates also added a lot of whimsy by including ballerinas, a giant duck reminiscent of Big Bird, puppies, baby chicks, a furry bear-like creature carrying a briefcase, and even an octopus. They’re so unexpected and, again, like Strictly No Elephants, gently humorous. And I also like the way that the illustrations mostly focus on the legs and feet of the people under the umbrella, rather than concentrating on their faces. It’s another subtle way to enforce this message of the beauty in diversity and yet at the same times it highlights the universality of living things: everyone wants to stay dry.

As far as the story or, rather, the message itself, I like that it’s really easy for young children to understand, and yet there are still a few excellent words to build up your child’s vocabulary, like “shelter,” and “plaid,” and “gather.” And I like that this could be a very simple story about being inclusive at school or at playgroup or wherever else your child might spend time, but that you can also use it as a tool to talk to your child who is on the older end of the target age range of this book about issues and concepts that relate to inclusiveness that are more difficult for young children to grasp, like, for example, immigration and xenophobia. The umbrella is a wonderful metaphor for the United States and how there are people who come to our country today seeking shelter, safety, and community, just as many of our grandparents or great-grandparents did just a generation or two ago. You can use this book to help you explain why a lot of the supposed “fears” people have about immigration are unfounded and often just a way to disguise xenophobia. Like the big umbrella, the United States has plenty of room for everyone. Some people think that there won’t be enough room for everyone in our society and economy, but there always is. So this book can be a good entry point for younger children into a discussion about immigration if your child has questions about what she sees in the news regarding people coming to our country to seek a better, safer, more promising future for themselves and their families.

Okay, our third book is Yo! Yes? which is both written and illustrated by Chris Raschka. I absolutely love this book because I think it’s just amazing how Chris Raschka gets so much across in so few words, only 34 to be exact—34 words!

Here’s what happens: The book actually starts in the end pages as one little boy who is white walks past another little boy who is Black. The little Black boy calls out to the little white boy who is sadly shuffling by with his hands in his pockets: he says cheerfully, “Yo!” And the other little boy responds, surprised, “Yes?” And the outgoing boy responds, “Hey!” And the white boy responds “Who?” And the Black boy exclaims, “You!” And the sad white boy is shocked and says, “Me?” And they go back and forth with only one or two words said by each boy on each page, but even through this minimal language, the Black boy comes to realize the white boy is sad because he has no friends—a problem the little Black boy solves immediately by saying, “Look! … Me!” And the white boy, finally getting over his disbelief and uncertainty that this other boy could possibly mean that he wants to be friends with him, says with obvious delight, “Yes!” And the book ends with the two boys jumping in the air together and exclaiming joyfully “Yow!”

It is the most delightful, short little book and I love it because it shows children just how easy it is to make a difference in a person’s life and how very few words it takes to make someone feel included and valued. The kindness and concern that the little Black boy demonstrates for the little white boy when he finds out that he has no friends and his genuine eagerness to then immediately befriend the unhappy boy is so, so heartwarming—it will make you and your child smile every time. And it’s such a great, clear model for our kids. You can talk about how the little Black boy notices the white boy, realizes how lonely he is, and simply offers to be his friend and that’s that. It’s not complicated and requires very minimal effort, but the payoff is huge for both boys. And, again, I love how economical and concise the dialogue is. There are no excess words and in fact some of the dialogue is just noises like, “hmm…” or “ohhh…” or even just punctuation like a question mark. It’s genius. And, actually, as far as helping our kids develop their reading and writing skills, it’s a great lesson in how punctuation and inflection work to get our meaning across in writing. So, if you have an early reader, this book is such an excellent choice on so many levels.

Yo! Yes? also earned a Caldecott Honor for its illustrations which I think is so well deserved, again, because they communicate the message of the book so elegantly and with such economy—the fact that they are so spare really complement the pared down text. There is basically no background, the illustrations are just of the two little boys themselves, and the boys are drawn on separate pages. But, what’s so great is that, as the story progresses, you notice how Raschka moves them from the far edges of their pages, closer and closer, until with the last “Yo!” “Yes!,” the little boys are joyfully shaking hands and it looks as if the little Black boy has pulled the little white boy over to join him on his page. And then the final page is the two of them together on one page, jumping in the air. It’s so subtle and clever, and this progression really underscores the lovely interplay between the two characters and the way that they become friends. And, just a side note, I think Chris Raschka is also so skillful at drawing children’s expressions and postures and attitudes and body language. I think my favorite illustration is the one on the page where the little Black boy is waiting for the little white boy to accept his friendship (it’s the page with the words “Yes, me!” on it). The little boy is standing there, shoes untied, this sweet, open, friendly look on his face, with his arms folded nonchalantly over the top of his head. It’s such a funny, characteristic posture for a young child and, as the mother of two little boys, I find it to just be so realistic and familiar and endearing.

And just one more thing before we move on: this would be a great book to talk to your child about befriending other children whom they encounter at school or on the playground who might not speak their same language. Because so much is done with gestures and inflection to build this friendship between the two boys, it again emphasizes to our kids how our actions can speak for us and how little we really have to say to make someone feel included.

Okay, onto Book #4 which is Three Cheers for Kid McGear! by Sherri Duskey Rinker and AG Ford. This is one of the companion books to the original, super popular Goodnight, Goodnight Construction Site book by the same author. If your child is a fan of the Construction Site books, she’ll love this one. The illustrations of Three Cheers for Kid McGear are done in the same whimsical, cheerful style as the earlier books, although this book works more within a yellow and orange color palette, which complements the energetic and cheerful Kid McGear character. And even if you haven’t read the other books by this author, if your child loves trucks and/or gadgetry she will also love seeing all of Kid McGear’s cool attachments and the way she zooms around the construction site.

So, first off, this might seem like an odd choice for a book about inclusiveness because for some reason what is usually emphasized when people talk about this book is this idea of how even the smallest person or truck can make a big impact. However, I really think being inclusive of others is the main message that the author intended to get across.

Here’s the plot: As the five original construction vehicles get to work on their latest job, a new truck arrives: a small skid steer named Kid McGear. Kid McGear is eager to help the crew with their construction job, but to her disappointment none of the trucks think she’s up to their rough and tough work and they all reject her offer to help. She dejectedly turns to leave, but then an emergency occurs that results in Excavator and Bulldozer being stuck under mud and rubble. Kid McGear is the first to come to their aid and, out of all the trucks, she, with all of her amazing attachments, is uniquely able to save the day. The book ends with her turning to leave again, but this time she is stopped by all of the other construction vehicles who ask her to stay and be part of their team. The last lines are:

Now Kid McGear has joined the crew.

Five old friends—and someone new!

SIX friends in the construction yard,

big and small, all working hard…

each one greater than they seem,

because they’re working as a team.

I like this emphasis on widening the friend circle and how the whole group is improved by the addition of another truck to their team. I think sometimes children—and adults for that matter—become reluctant to open their friend circle not necessarily out of malice, but just because they’re comfortable in their peer group and therefore don’t think to, or feel the need to, expand it. So, it’s nice that this book reminds our kids that new friends can be so valuable and that their lives can be further enriched when they open up and allow someone new with new perspectives and talents and ideas to join their circle of friends.

And it’s also great that this book shows that if you let someone new in, it doesn’t mean that you have to abandon your old friends or that your old friends will abandon you. This can sometimes be a concern for very young children, so it’s reassuring for them to see this successful example of a friend circle expanding where no one is excluded or left out or forgotten because someone new has joined.

I also like this book because Kid McGear can not only represent people who are younger and less strong who are excluded from the group (like how sometimes older siblings will exclude younger siblings), but she can also represent people who are excluded because they are differently abled. Kid McGear is rejected at first not because the other 5 vehicles don’t like her, but because they worry that she’ll injure herself on the job. This book can help us to call attention to the fact that there are all kinds of ways to exclude people, and that even when we believe we’re being thoughtful, we could be being hurtful. I like that the book shows how Kid McGear’s small size and many attachments are not hindrances to the work at all, but are actually really helpful not only to Kid McGear but also to the whole group.

And just one more thing about this book before we move on: I love that Kid McGear is a female vehicle. My main criticism with the original Goodnight, Goodnight Construction Site picture book was that none of the trucks was personified as female, which I think was a huge missed opportunity. Evidently, the author and publisher must have heard this a lot, because in its sequel Mighty, Mighty Construction Site (which was published in 2017) some female trucks were introduced, although they didn’t officially join the crew, they just came to help out with a big construction job. And then, unfortunately, there were no female trucks included in the Construction Site on Christmas Night book which was published in 2018, which, again, was disappointing. It’s seems like a no-brainer to me to make sure that you always include a female truck. In any case, I like that in this one, a female is not only introduced, but she takes center stage. All I can say is: It’s. About. Time.

Calvin Can’t Fly: The Story of a Bookworm Birdie

Okay, the 5th book that I’d like to recommend is called Calvin Can’t Fly: The Story of a Bookworm Birdie by Jennifer Berne and illustrated by Keith Bendis. This book is about a starling named Calvin. Unlike his many brothers and sisters and cousins who fall out of the nest to discover the world of worms, grass, dirt, and water, and who learn how to swoop, hover, and fly figure eights, Calvin discovers the enchanting and informative world of literature and spends his first summer of life with his beak in a book—reading, learning, and absorbing everything his little startling mind can. Some of the other birds make fun of him and he feels lonely and ostracized, feelings which only get worse when the other starlings head south for the winter and Calvin, who hasn’t learned how to fly, thinks he will be left behind. But then his sisters, brothers, and cousins return with string and scraps of cloth to scoop him up and fly him south in a makeshift sling. All seems well until the air develops an odd smell, the smell of DANGER. Calvin, who remembers what he learned in his favorite weather book, is the only one of the flock to recognize the impending hurricane for what it is and he hastily instructs his family on what to do. Because of Calvin, the entire, enormous flock of starlings is saved from the hurricane and they all have a giant starling party in his honor. Calvin is so happy that he jumps and flaps his wings and discovers that he can fly after all. The book ends with Calvin and his family all flying joyfully south for the winter and the back cover shows Calvin and his siblings in their family nest, all of their beaks buried in a variety of books.

I love this book’s take on inclusiveness because it incorporates both a personality difference and also an ability difference. Calvin Can’t Fly can be an entry point for you to talk to your child about being accepting, supportive, and inclusive of her friends who may have, say, a learning disorder or a physical disability. Just because Calvin can’t fly and just because he expresses himself differently than the other starlings doesn’t mean that he has to be left behind or that he isn’t interested in being a part of the group. So, this book can help you teach your child how to reach out and include peers who might be differently abled or who express themselves differently in their play.

This book is an especially valuable resource for preschool or kindergarten-aged children. When it comes to different abilities, even if the difference isn’t so marked as it might be with a child who has a severe physical limitation or learning disorder, this book can help a young child to make sense of her world in which some of her peers may not be as advanced as she is in certain areas, but in other areas they may be more advanced than she is, and to understand that both are okay. Particularly in preschool and kindergarten, there is a very wide range of physical abilities and social-emotional skills among children of this age group. Some children may be able to ride a bicycle and tie their shoes, but they don’t yet know their alphabet and numbers—or, they might still get anxious when they hear loud noises. While other children may be able to read, but they have trouble recognizing emotions in others or they can’t zip up their coats. So, Calvin’s story can reinforce the message to be accepting of everyone and to include everyone in their play, even if some have varying levels of ability or different communication skills.

For example, I like that in this book, while the other birds just tell Calvin he’d better learn to fly and leave him to his own devices, assuming he just doesn’t want to come along with them, Calvin’s sister is more observant and therefore more discerning. She asks Calvin directly, “Calvin, can you fly?” and then, understanding that it isn’t a matter of not wanting to fly away with the others, but of ability, she apparently conspires with the other birds behind the scenes to include Calvin in their migration by literally carrying him along with them. It’s a great model for children to learn that when they are faced with a situation where one friend can’t participate on the same level as the others, they can problem-solve instead of just saying oh, well, this friend or sibling or classmate can’t do this activity with us so we just won’t include her. This book can help children to understand that the right thing to do is to brainstorm and find a way to include that person in the activity or to choose another activity because the most important thing is to make sure no one is left out or feels excluded.

And I also love that Calvin, even though he eventually does learn to fly, still remains true to himself and is valued by the group not because of his newfound ability to fly, but because they recognize that his differences make the group better and stronger. Again, it’s so important to emphasize to our kids that diversity and difference just make us all better and our lives richer. The episode with the hurricane is such a brilliant way to get this message across because without Calvin and his widespread knowledge that he gained by being a bookworm, the entire flock would have been lost. And it’s great that even though the other birds have no idea what a hurricane is and they can’t understand all the words Calvin uses to explain it to them, they trust Calvin because despite their differences, he is one of the group and they know that they’re all on the same team and that they can all benefit from Calvin’s unique skillset.

And finally, I also really appreciate that this book is slyly humorous in a way that adults will find amusing, too. The illustrations are done in pencil and watercolor, but the style is almost like a New Yorker cartoon in the way Keith Bendis draws the birds’ and other animals’ expressions and habitats. I particularly love the illustration of the library in a tree which has a sign for regular hours and nocturnal hours. And Calvin’s dialogue is so funny. He’s so erudite and formal when he speaks, like when the other birds taunt him and he reacts with an almost Shakespearian response “Oh, how the wounding words of scorn do sting;” and like when the other birds tell him that he needs to start flying because they have to be out of the barn in a few days, and he responds “Ah yes, migration. I’ve read about that.” It makes me laugh because it reminds me so much of life in academia and so much of some of my former professors whom I found so endearing, but about whom I also worried when they had to, you know, like, drive a car or something. One of my professors for whom I was a Teaching Fellow was so, so brilliant—probably one of the smartest people I’ve ever known—but one day I was 2 minutes late to class because a student had stopped me on the way to give me his paper because he was leaving early for break, and anyway, I came in to the classroom and found this professor and all of our students sitting in the dark because he couldn’t figure out how to turn on the lights. It was adorable. Ah, I miss that man.

Okay, anyway, up next is a book called Brontorina, by James Howe and illustrated by Randy Cecil. This book is about a dinosaur named Brontorina Apatosaurus who has a dream: she wants to be a ballerina. Brontorina goes to Madame Lucille’s Dance Academy for Girls and Boys and despite Madame Lucille’s initial misgivings, with the prompting of two little children named Clara and Jack, the dance instructor welcomes Brontorina to the class. Two of the little girls in the academy, however, are not happy about it, claiming Brontorina is too big and doesn’t have the right shoes. Brontorina definitely has talent, but she has trouble moving in the studio, making some of the students nervous during her arabesques, knocking a few holes in the ceiling during her relevés and jetés, and finally crushing the piano in an unfortunate fall. Madame Lucille sadly decides that Brontorina must leave the academy, but as she turns to leave, Clara’s mother arrives with some dinosaur-sized ballet shoes. This small act of empathy and kindness prompts Madame Lucille to realize that it’s not that Brontorina is too big, but that her studio is too small. Madame Lucille and the children go on a search for a bigger studio and end up creating a new and improved one on a large, open farm. The dance sign for the studio now reads, Madame Lucille’s Outdoor Dance Academy for Girls and Boys and Dinosaurs and Cows. Shoes, All Sizes.

Before we get into the story itself, I just want to say that I think the illustration style of this book is so interesting and engaging. Brontorina’s sweet, eager face is so endearing and her expressions when she tries gracefully to hold her poses while knocking into the ceiling and trying not to crush the other children are so hilariously rendered. I also find the almost Piccasso-like abstractness of the human faces to be surprisingly charming and I like the way the delicate details and muted colors contrast with Brontorina’s large, orange dinosaur body. I can’t figure out what painter Randy Cecil’s style reminds me of the most—I think a little bit of Piccasso and a little bit of Georges Seurat and a little bit of Fernando Botero, but there’s definitely another artist that I can’t put my finger on. If you have any ideas, email me or dm me please because it’s been driving me crazy. In any case, I really, really like the style of these illustrations and the way Randy Cecil uses light and color to convey the moods and messages of this book.

Anyway, as far as helping us to teach our children to be inclusive of others, this book is great because it not only addresses Brontorina’s size, but also the fact that she doesn’t have the same shoes as everyone else. We talked about how size is often a reason a child is ostracized from a group with Three Cheers for Kid McGear, so I won’t go into it too much again here. However, I’ll just say that being “too big” is another very common reason that children are excluded by other children and often this isn’t looked upon as discrimination because many people wrongly feel that size is somehow the child’s choice, rather than the result of socio-economic factors and things like psychological trauma or biological factors like metabolism and pre-existing health conditions. Research has shown that overweight children are more likely to be excluded from friendships than children who are of average weight or underweight and these children are also more likely to call their classmates friends when the feeling is not mutual. A study by the University of Southern California has shown that this exclusion can increase the risk of loneliness, depression, poor eating habits, and illness for the children who are ostracized. So, it’s crucial that we talk to our children about being inclusive of people of all sizes AND to make sure that we as adults model acceptance of people of all sizes and that we don’t speak negatively about people’s weight, including our own.

Besides this, reading Brontorina can also be a way to help your child become aware of discrimination and exclusion based upon a child’s economic status. Brontorina’s shoes (or lack thereof) are the other reason that the two little girls criticize her and that Brontorina feels like she doesn’t belong in the dance academy. It might seem that your child is too young to discuss complex issues like income inequality and poverty, but the fact of the matter is, even very young children notice disparities in wealth. After all, childhood has become even more commercialized and materialistic in the past two decades while at the same time income inequality has widened in our country. So even though wealth and income disparity segregations are difficult subjects for us to discuss with other adults let alone with children, it’s still our job as parents and caretakers to help children navigate these subjects so that they don’t create biases based upon their own false assumptions. In order for things to change, we have to talk to our kids about what society values and to call into question whether it rewards the right things.

Again, this may seem daunting to do with a four-year-old, but don’t worry: first of all, you don’t have to give kids too much information at once. This is an ongoing conversation that will happen throughout your child’s life. And second, books like this one can help you. By using age-appropriate language and examples, you can help your child to start recognizing and understanding these issues. The conversation will get deeper and more nuanced as your child gets older, but what you can do right now while reading this book is simply help your child to notice the stigma attached to Brontorina for not having the same shoes as everyone else and how this is unkind and unfair. For example, you can point out how the words of the two little girls (“She is too big” and “She doesn’t have the right shoes”), even though they are ostensibly making observations about Brontorina and not saying these things directly to her, are still hurtful and damaging to Brontorina’s self-worth. When you read the little girls’ comments, you can say, “Oh, what an unkind thing to say! Brontorina can’t help that she doesn’t have shoes that fit her feet. That must have really hurt her feelings. Look how sad she is.” And then you can talk about why Brontorina might not be able to get ballet shoes—whether it’s because they don’t exist in her size, or she can’t afford to buy them, and why both of these scenarios are unfair. And then you can also say as an aside to your child, “Isn’t it so great that Clara and Jack stick up for Brontorina? They are being such good friends! They like her just the way she is.” And then, you can make sure that you also talk about how Brontorina may not have the right shoes, but that Madame Lucille is so excited because she sees that Brontorina is an innately graceful dancer who is truly a ballerina no matter what she has on her feet. And even when Brontorina is given the ballet slippers by Clara’s mom, at the end of the day, the kids and Madame Lucille realize that the problem isn’t Brontorina’s size or her shoes at all. It’s that the ballet studio is just too small and doesn’t offer shoes for everyone; that’s what needs to change, not Brontorina.

In this way, you can also help your child see that exclusion and discrimination negatively affect everyone, not just the target. In four-year-old language, this just means pointing out that because they don’t try to make a space that will fit everyone from the beginning, the piano gets smashed and Brontorina and the other children can’t dance together without worrying about running into each other. Or, it just means when you finish the book, simply commenting, “Wow! Look! Now the dance academy is outside in the sunshine! And look at all the other kinds of dinosaurs that are part of the class now that they made it so everyone could fit! Wouldn’t it be so cool to have dinosaurs at your dance academy? And, oh my goodness, look! Now cows can dance, too! That’s so fun! And now everyone can have a pair of shoes that fits their feet—isn’t that just great?”

And finally, just one last thing about Brontorina before we move on: I like that this book has children showing the teacher how to be inclusive. The sad truth is, many adults that your children will encounter throughout their young lives will have biases and it’s important for kids to learn how to advocate for themselves and for other children if they see something happening that they know isn’t right. I like that this book shows two kids, Clara and Jack, who don’t give up on including Brontorina in their group, even when Madame Lucille doesn’t see a way to do it. The story of Brontorina is such a great example of children successfully advocating for their peers.

Okay, next up is another one of our favorite books in our family and that is Red: A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall. This book was given to James, actually before he was born, by my friend Kevin and his husband Jonathan and we all just love it. If you’re listening, thank you again Kevinaki—it’s such a brilliant book and an awesome, unique choice for a baby shower book because it spans a really wide age range and it’s one your child will appreciate on many levels for years to come. So if you’re looking for a great baby shower book, this is an excellent choice.

The story is about a crayon whose label says he’s red, but the color underneath doesn’t match the label. His teacher, his parents, various art supplies, and his crayon peers all try to help him be red and draw red things. His teacher, a crayon labeled Scarlet, helps him practice drawing strawberries; his mother, Olive, sends him on a playdate with Yellow to draw an orange together; his grandmother, Silver, tries giving him a red scarf to wear; the scissors tries snipping his label in case it’s too tight; and even his friend pencil (who is also the narrator of the story) tries sharpening him with a pencil sharpener. But no matter what they do and no matter how hard he tries, he just can’t be red and he’s miserable about it, feeling like he just doesn’t belong. But then he meets a new friend labeled Berry, who asks him to draw a blue ocean for her boat. At first, he’s confused and says, “I can’t. I’m red.” But after some coaxing, he does and discovers what the reader has known all along: he’s blue! And the book ends with him happily coloring all kinds of blue objects and he is embraced by the rest of the crayons for who he truly is: Blue.

This book actually made me cry when I first read it and it still does occasionally, especially right now when the rights of the LGBTQ community are constantly being threatened by this political administration and there is so much violence occurring against trans people.

Anyway, I love Red: A Crayon’s Story because its message is so simple, so direct, and so obvious that your child will understand it right away. What the other crayons and art supplies fail to see when they try to “help” or “fix” the crayon, but what the child reader will see right away, is that the crayon is simply mislabeled. He’s a blue crayon. He can’t possibly be anything else, no matter how hard he tries or how much he wants to, because he’s blue. The fact that his label says “RED” doesn’t change what he is.

Therefore, this book is a really excellent way to start talking to young children about gender identity, gender expression, and gender non-conformity and also about ways to make sure people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond to their birth sex feel supported and included. The crayon protagonist of this book “presents” as red, but colors blue, just as a transgender person may “present” as male, but identify as female. I just think Michael Hall’s use of a mislabeled crayon is such a brilliant, effective way to get this idea across to very young children—although, I have to say, I don’t think this book has an upper age limit if you’re using it as a tool to explain gender identity to someone. This book works really well to illustrate this concept to adults, too. So if your young child—or your older child—has a transgender person in their class, or you have a transgender person in your family or friend circle, or even if you just encounter a person who is transgender while you’re out and about, this book is an excellent tool to help you answer questions that your child might have. And by the way, you might think that this is a conversation that you wouldn’t need to have with a preschooler, but I’ve already had this conversation with my then two-and-a-half-year-old son because the first time he met a trans woman was while we were out shopping. She was the cashier and she kindly gave my son a sticker and when we got back to the car, he said, “Mommy, was that a lady who gave me my sticker or a man?” And so, literally with the help of this book because I referred back to it, I explained that just like the blue crayon was really blue, but people thought he was red because he came from the factory with a red label, when the person we saw that day was born, people thought she was a boy, but she knew that she was actually a girl, so she is a girl. It actually made the conversation really easy for me to have and the concept understandable for my toddler. Now, my answer probably wasn’t perfect in its explanation or in its execution because quite frankly, I wasn’t prepared for my son’s question and so I was kind of flying by the seat of my pants, but for that moment and for my child, it was enough. He was satisfied with my answer because he had already digested the information that a crayon can be mislabeled, so if it can happen to a crayon, why couldn’t it happen to people, too? So I personally am really grateful to this book for helping me to talk to my child about trans people in an age-appropriate, uncomplicated way.

I also really like that this book shows children a subtle and even unintentional way that people are made to feel like they don’t belong. When the other crayons gossip about the mislabeled crayon amongst themselves, saying that he doesn’t apply himself or wondering whether something is wrong with him or simply just saying “Give him time. He’ll catch on,” even if their words aren’t necessarily cruel or critical, it still makes the crayon feel isolated, ashamed, and sad. So this is an important piece of information for our children: when we try to “fix” or “help” someone rather than simply accept and celebrate them for who they are, we are not being inclusive.

So I LOVE that this book could be a way to talk about what it means for someone to be transgender and how to be supportive and inclusive of that person, but I also like that there’s also so much else to talk about, like gender roles, the importance of being respectful and celebrating someone’s true self and their true talents, and the idea of not judging people based on their appearances.

For example, our kids are bombarded with information about gender roles from pretty much the day they’re born. From clothes to toys to extracurricular activities to television shows to bedroom decorations—even to books—in so many ways, society tells us how girls and boys are supposed to look, dress, act, and even speak. If we want to raise people who feel free to express themselves, who feel that they can accomplish anything no matter their gender, and who appreciate and respect the contributions to the world made by people of all genders, it’s really important that we start sending these messages to our kids early on in their lives and this book can really help you open up this conversation with your child. Red: A Crayon Story can provide you with an opportunity to talk to your child not only about empathy and being sensitive to the feelings of others by asking her questions about how she would feel if her name or her gender or her identity was mislabeled (by saying things like “How would you feel if someone called you by the wrong name or called you a boy instead of a girl?”), BUT ALSO, this book can give us a great entry point into a conversation about your child’s own ideas about gender roles and help you correct any biases that she may have inadvertently picked up. You can ask her how she would feel or what she would start to think about herself and her capabilities if someone told her she couldn’t do something because she is a girl or that she HAD to do something because she is a girl. For example, you could say, “What would you start to think if someone told you that you can’t ride your bicycle because girls aren’t good at riding bikes? How would that make you feel?” And this way you can brainstorm and problem solve with your child before she actually encounters this situation in her real life.

Okay, before we move on, I just want to highlight one more thing about Red: A Crayon’s Story: I like that Michael Hall gives the reader the equal and opposite of the two-page spread where all the different crayons are gossiping about and criticizing the mislabeled crayon. At the end, he gives us a two-page spread of all the crayons being supportive and admiring of the blue coloring crayon and they celebrate his true identity. This, again, is such a great model for kids–and for us. Even though this moment is perhaps idealized in the book because in reality celebration and support are not currently the normal reaction, this is how we should act when someone tells us his true identity and I’m hopeful that if we model this for our kids now, when they are adults this will become the normal, automatic response.

Okay, so onto our last two books. If you have younger children, like, toddler-aged children, there are two books that I recommend that manage to get this idea of inclusion across for very young children and the first is But Not the Hippopotamus by Sandra Boynton. I talked a lot about Sandra Boynton and why her books are so perfect for toddlers and their cognitive and social-emotional development in Episode 1, so if you’d like to learn more about that, I recommend you go back and listen to that episode.

Like all of Boyton’s books, But Not The Hippopotamus is illustrated in her characteristic style and it’s concise, humorous, and has a slight wackiness to it. In this book, all the animals not only have a rhyming partner (like the hog and the frog, the moose and the goose, the cats and rats, the hare and the bear), but they all are engaged in activities with each other (the hog and frog cavort in a bog, the moose and goose together have juice). All except, that is, for the hippopotamus, who is shown hiding behind a tree, eating alone at a table, and peering in the shop window at the cat and the two rats. All of the animals go on a jog without the hippopotamus, but then they circle back to her and say “hey, come join the lot of us!” She hesitates and deliberates, but then Boynton continues joyfully “But YES the hippopotamus.” And she joins in the jog. All is well, except the last line which returns us to the dilemma. “But not the armadillo.”

First off, I have to tell you that Sandra Boynton has said in an article for the Wall Street Journal that she didn’t look at it as the Hippo being excluded by the other animals, but rather that she is a self-excluding hippopotamus. And in the sequel to this book, But Not the Armadillo, the armadillo chooses to be—and is happy to be—on his own. However, in this book, whether the hippo is being excluded or excludes herself, it’s a good way to teach small kids to always ask just in case the person wants to join in their play.

Sandra Boynton is so great at capturing human emotion on her animal’s faces, so this book is an excellent way to show your very young child how people respond and feel when they are left out.

I like how Boynton gently nudges the reader to sympathize with the hippopotamus, showing rather than telling the reader, through the images but also through the rhyming text, how it can sometimes be difficult to be different in a world where everyone else seems to rhyme and fit in. It’s such a great way to introduce ideas about diversity and inclusion to little kids without it getting the least bit overwhelming or it just going completely over their heads.

And, if I can just look at this book from the point of view of an adult for a second, I actually kind of like the ending with the armadillo, even before you read the sequel and realize the armadillo is content to be alone, because the other way you can look at it is that the work of inclusion is never over. We have to keep on trying to be inclusive of everyone. So when you read this book to your child, you can say something like, “Oh dear! Now the armadillo is left out! Do you think they should ask the armadillo to run with them, too? … You do? Yes, I think so, too!”

And just one more quick, unrelated thing before we move on to our very last book: I like that even in a very simple book for very young children, Sandra Boynton doesn’t compromise on vocabulary. She picks the perfect word, even if it isn’t one that is used in everyday speech, like, for example, “cavort,” or “bog,” or “scurrying.” This is so great for a small child’s vocabulary acquisition and I just love that Sandra Boynton is such a stickler for the perfect word.

Okay, our last book, Egg, by Kevin Henkes, also comes in board book form and, like But Not the Hippopotamus, it works really well for toddlers. Here is the story: There are four eggs, one pink, one yellow, one blue, and one green. The pink, yellow, and blue eggs hatch open to reveal three baby birds, but the green egg remains an egg, waiting, and waiting, and waiting. The three little birds examine, listen, and peck at it, until finally, finally it hatches and… out pops a green baby crocodile! The three little fledglings fly away in alarm, leaving the baby crocodile alone, sad, lonely, and miserable (each emotion is depicted in its own square in the illustrations). The three little birds, flying above the baby crocodile, notice his misery and slowly, tentatively return one by one to perch on his back. The word “friends” labels the image of all three birds happily twittering atop the smiling crocodile and then the crocodile paddles them out into the water where they all look at the peachy-orange sun and imagine it to be an egg. “The end…” the book says, but then on the last page, there is a peachy orange bird flying in the sky and the story ends with the word “maybe.”

This book is such a great introduction to difference and inclusion for toddlers and preschoolers because it is so simple in its design and plot and it is also so straightforward and relatable when depicting emotion. Henkes clearly portrays both the initial uncertainty of the birds and the abject loneliness of the crocodile in such an understanding, sympathetic way. I like how Henkes shows the pink bird overcoming his or her timidity and gently landing on the crocodile, which encourages the other two birds to follow suit. It underlines this idea that it only takes one person to make a difference and to lead the way for everyone to have an attitude of openness and inclusiveness. It’s such an empowering message for little kids.

As far as the text itself, there is a lot of repetition, which also makes it perfect for toddlers, but also for preschoolers who are learning to read. Most of the words are short and easy to sound out. But there are also words that will stretch a child’s vocabulary and reading ability, like “lonely” and “miserable.”

The illustrations are also so sweet and clever. Again, the drawings are great for recognizing emotions, and they show your child what it feels like and looks like to be alone, sad, lonely, and miserable. But also, this book is very unique in its style for this age group—it really is more like a graphic novel for toddlers and preschoolers than a picture book in the way the images and text are laid out. Each eggshell-white page is framed with a chocolate-brown border and there are a lot of smaller frames within many of the larger framed pages that help support the story by, for example, suggesting the passage of time, like on the page with 12 framed identical green eggs labeled “waiting” or by showing the crocodile’s deepening despair on the page with four framed images of the crocodile looking increasingly unhappy that are labeled “alone,” “sad,” “lonely,” and “miserable.” And I just really love the pastel color palette with the robin’s egg blue, creamy yellow, and baby pink birds and the pale green crocodile all outlined in black, again through color and style showing that they all belong together. It’s a really exceptional, unique, and interesting book for very small children both visually and in its story, so I think Egg would be a great choice to start introducing your toddler to the concepts of diversity and inclusion and it also would just be a great addition to your family’s collection.

And that’s it for this episode of the Exquisitely Ever After podcast. As always, please visit the show notes at, ExquisitelyEverAfter.com/episode9 for a complete list of the books that were mentioned today and, if you haven’t already, you can also download my free PDF of 50 Diverse Picture Books to read to your child there, too. And if you liked this episode or this podcast in general, please do subscribe, it’s totally free and by subscribing you ensure that you don’t miss any new episodes. AND, if you have a minute, please leave me a review and also please tell a friend! You can share episodes via text or email and for a new show like mine, this kind of word-of-mouth recommendation helps so, so much to get my podcast into the ears of more people. I really appreciate that you took time to listen to me talk about reading children’s literature today! And I really hope that these nine books are helpful to you in your efforts to raise an inclusive child. And I would love to hear about any books that you think are great for teaching our little ones to celebrate diversity and be inclusive of others. Please send me an email at christina@exquisitelyeverafter.com or dm me on Instagram at exquisitelyeverafter or leave me a comment on the blog post for this episode, at exquisitelyeverafter.com/episode9.

Thanks so much, everyone! Take care, keep safe, and keep reading!

Wait, you guys, I just had to jump back on here and tell you that I just thought of the artist and painting that the Brontorina illustrations remind me of. The artist’s name is Gustave Caillebotte and I literally had a print of his painting entitled The Floor Scrapers hanging in my apartment during all 8 years of graduate school. I swear, this pandemic is really taking its toll on my brain. Or maybe it’s just having children. Anyway, I’ll put a link to The Floor Scrapers in the shownotes so you can check it out and see if it reminds you of the Brontorina dance studio, too. Happy Reading, Everyone!

Pin This Episode For Later: